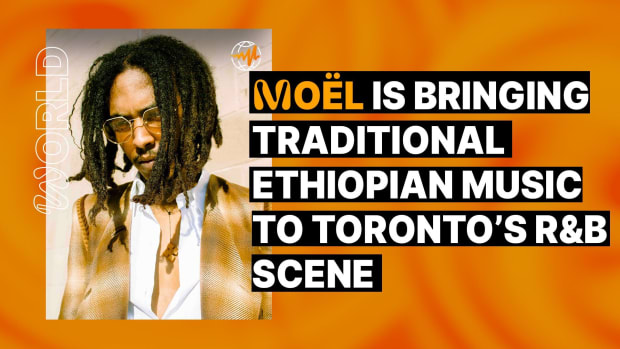

Toronto R&B artist Moël speaks with Audiomack about expanding the traditional Ethiopian sound into the city’s R&B scene.

This article previously appeared on Audiomack World.

Moël’s musical origin story is so quaint that you’d think he lifted it from a direct-to-TV movie. He was walking down the street in Calgary in 2014, where his family had recently immigrated from Ethiopia, and he happened across a street performer. On a whim, he took out his guitar, sat down with the busker, and started playing along. “Let’s make a band,” the street performer proposed. This union never materialized, but according to Moël, it was this experience that inspired him to become a performer. “It showed me I could go anywhere and make something,” he says.

For the 24-year-old singer-songwriter who now resides in Toronto, this type of anecdote is typical. From the path he follows to the music he creates, Moël takes his cues from the universe. “Music is at the tip of every moment,” he explains. “If you decide to get excited about it, it’s right at the tip, and you can chase it.”

Across the two EPs he’s released to date, 2019’s Kopia and 2020’s Red Red Sea, Moël has done just this. The former is an earthy project brimming with potential, while the latter pulls from a wider variety of reference points, melding contemporary R&B music with the influence of Bob Dylan and sounds from Moël’s native Ethiopia.

Asked about uniting these influences, Moël gently dismisses the idea, understandably wary of being pigeonholed. He never set out to record songs in Amharic to make a statement, he explains. He was simply responding to a feeling—trying, in his words, to “paint the world.”

It just so happens that, in the process of painting the world, Moël is making the sounds of traditional Ethiopian music more accessible to a Western audience and boosting East African music’s global recognition along the way. His desire not to be put in a box is understandable, but with such an expansive appeal, the odds he can ever be boxed-in successfully are slim to none.

Why don’t we start with your upbringing? What kind of music were you listening to growing up in Ethiopia?

I was listening to a lot of Afrobeats, Ed Sheeran, and Daughtry. I don’t know if you know Daughtry, but the first song I learned was “Home.” That song is the reason I play guitar.

I would never have guessed that. Does that mean you weren’t listening to a lot of R&B?

Yeah, I started listening to R&B a little bit before I moved to Toronto. I got introduced to it when I was in Calgary with Daniel Caesar. That’s the reason I moved to Toronto, actually. I started listening to that, and I knew there was a sound I could explore over here. I made a few songs when I was in Calgary, but I saw something bigger, and so I came out here and figured it out. I met some people, and I got into more Frank Ocean, Brent Faiyaz, Miguel, and music like that.

People classify my music as R&B, but even today, I don’t necessarily listen to a lot of it. I like Playboi Carti. I like Nipsey Hussle. I like Isaiah Rashad. I like specific people who carry a vision.

What was the moment you realized you wanted to start writing and performing music?

It was probably after I got to Calgary. I saw this guy playing on the street—he had a guitar and he was just jamming—I started talking to him, and I played with him. And he was like, ‘Yo, let’s make a band.’ We never did, but that showed me I could just go anywhere and make something.

Tell me about the themes you like to explore in your music.

I’d like to be more diverse. I’ve been thinking about all the things that are going on in the world, and I’d like to talk about those things. But, most of the time, it just comes back to love. Whether it’s a sad love song or something else, a love song can be very diverse. It doesn’t have to be about a girl; it could be about anything.

On your first project, Kopia, you were singing almost exclusively in English. But on the newer EP, Red Red Sea, you started singing in Amharic. What made you want to make that jump?

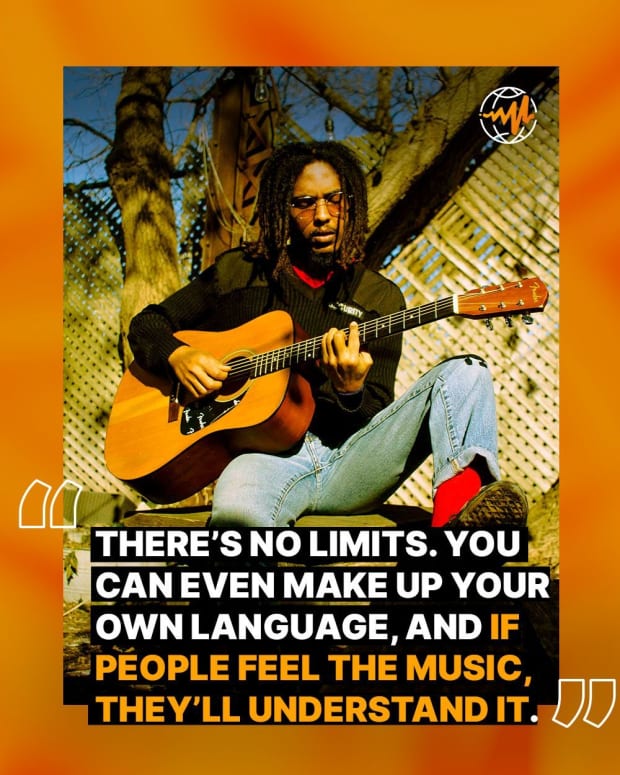

I think it was just a shift of perspective that happened. My sister would always tell me, “Leave the Ethiopian music, and focus on the English because that’s where it’s at.” But we got to a point where the music felt so easy to make. It’s really just sounds, and it adds energy. There’s no limits. You can even make up your own language, and if people feel the music, they’ll understand it.

From what I’ve heard of Ethiopian music in the past, I hear its influence a lot in the vocal runs and phrasing you use, particularly on a song like “Damage.” Would you agree with that?

Definitely. It’s all rooted in the Church. That’s where music comes from. The first person who played music was [sixth-century Ethiopian composer] Yared. Once you hear that type of music—[hums]—that type of spiritual music, and you’ve been in the Church, and it’s resonated with you, it just reflects in the music. You hear that with The Weeknd and Tilahun Gessesse, and all the best people, you know?

Would you say your goal is to make Ethiopian music more accessible to a mainstream audience?

I think that’s something people are getting, but that was never the goal. I’m just trying to paint the world. I want to design something people can live in, an environment. I have the Ethiopian experience, so that may come in, but the music started way before that.

Why do you think East African music has lagged behind West African music in terms of global recognition?

I think West African music is just going right now. It’s got a good rhythm, and it’s what people are feeling. There’s a lot of good East African music, even outside of Ethiopia. There’s a rapper I like named Kassmasse. But it doesn’t have the same impact because it doesn’t have the same rhythm. Nigerian music is very unique. You don’t have to understand the words; you can just follow it.

When people ask you questions like these, does it feel like you’re being put in a box because of your identity? Does that ever get annoying?

Yours is actually a pretty good box. Sometimes, the box is a lot smaller.

What’s next for you? Where do you see yourself in the next five years or so?

Do you like Bob Dylan’s music? I’ve been watching these music documentaries recently, and that’s how I’d like things to go musically. Whatever we put out, I want it to be on our time, and if people gravitate towards it, that’s the way to go. I just want to make something better every time. Just better music and better energy.

Go to Source

Author: Hershal Pandya